Without better client diagnostics, direct indexing has limited upside

Read time 5 minutes

In this Post:

- Tax Loss Harvesting is Now Table Stakes

- Client Diagnostics Will Differentiate Direct Indexing

- Current Client Diagnostics are Not Up to the Personalization Task

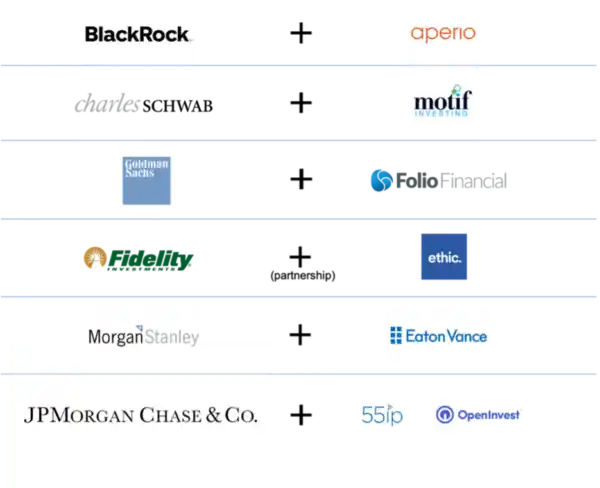

Direct indexing is hot. The 800 lb. gorillas of asset and wealth management have been snapping up (or partnering with) direct indexing outfits.

There are two main reasons for the frenzy:

- Direct indexing technology makes tax loss harvesting affordable and efficient for larger swathes of investors (down to and including high-net worth segments).

- Direct indexing enables the ultimate in personalized portfolio construction. Many asset and wealth managers see personalization as a new frontier in value-add (so do we).

There’s real economic value to be unlocked in both cases. But each comes with a strategic danger, too.

In my view, tax loss harvesting will be a competitive wash in the direct indexing fracas. Those who emerge as winners will have invested in next generation client diagnostics to unlock the value of their (newly acquired) portfolio personalization machinery.

Tax Loss Harvesting is Now Table Stakes

Take tax loss harvesting first. All major players will soon offer direct indexing to their clients. It’s impressive technology, to be sure, but there’s nothing especially differentiating about tax loss harvesting machinery itself, or the financial benefit to a client. The same client could reasonably expect to go to any of the major wealth management shops and benefit roughly the same from tax loss harvesting.

The upshot is this – tax loss harvesting has just become table stakes. All the major players will offer it, and there’s very little scope for differentiation there.

Client Diagnostics will Differentiate Direct Indexing

That brings us to personalization. Many (including the team here at Capital Preferences) see personalization as one of the next great frontiers of value-add in wealth management. After all, direct indexing enables the ultimate in personalized portfolios.

Add in the sustainable investing megatrend (as players like OpenInvest and Ethic have done), and the industry is really onto something. It can help people align their investments with their values at a time when the earth needs it most…and when humanity appears to be going through a pandemic-aided, once-in-a-generation shift in ESG consciousness.

Here’s the problem: lack of suitable diagnostics will keep direct indexing’s personalization value all bottled up. Clearly, the limiting factor will not be the granularity of portfolio that can be constructed. With direct indexing, the keen investor can exclude or include individual stocks to their heart’s content.

Direct indexing’s limiting factor will be the granularity with which investors can discover, understand and communicate their own preferences.

Most investors have a hard time expressing their exact preferences, especially in ambiguous, new domains like ESG. Many of them know they want to make an impact with their money, but beyond that, aren’t sure in exactly which ESG domains or through which ESG vehicles.

That’s why unlocking personalization value will depend on the state of client diagnostics.

Current Client Diagnostics are Not Up to the Personalization Task

Most of the wealth management industry is still using dated approaches to understand clients’ preferences. With risk preferences, for example, around two-thirds of clients engage in “dialogue” with their advisor and/or answer a questionnaire (most of the rest don’t remember or were never risk profiled at all). These are both “stated preferences” methods that are well-known to be rife with bias and imprecision. Not what you’d want to be using to “hyper-personalize” your client’s portfolio.

And when it comes to understanding ESG preferences, the industry is using the same kinds of questionnaires and dialogue. That’s perhaps more understandable (but no more defensible), in that understanding investors’ ESG preferences is a more recent thing than understanding their risk preferences.

Take a step back and think about the absurdity of it.

We now have the machinery to construct uniquely personalized portfolios.

But we’re still asking clients to rate their own risk tolerance? Or rate E, S and G themes on a 3-point scale of “not important”, “important” or “very important”? (I’m not kidding. The robo-advisor that won Investopedia’s “Best for Sustainable Investing” award has its clients do this exact exercise).

This is where we are?

It’d be like going to a Nike store to order brand new, one-of-a-kind, hyper-personalized Nike-by-You athletic shoes—because they can hug your feet like no shoe ever has. And the color of the lace loops can match the mudguard window (yes, that’s a thing). And on the sides, you can custom screen print your neighbor’s best-friend’s dolphin artwork.

The clerk winks, gives you a knowing nod, reaches under the counter, and pulls out one of these.

“Let me just get your footsize…and you’ll be Good. To. Go.”

*jaw hits floor*

That doesn’t work. It’s not up to the task. There’s no way THAT instrument can land me in my hyper-personalized fantasy shoes.

By the same token, the industry’s current diagnostic approach simply isn’t up to the task of understanding clients precisely and accurately enough to put them in uniquely personalized portfolios.

In my next post here, I unpack what’s needed in client diagnostics to rise to the direct indexing occasion. And, we have more fun with the personalized shoe example.